House in Sanbancho

Sanbancho, Chiyoda, Tokyo, Japan, 2023—2024

The picture of the city that we carry in our mind is always slightly out of date.

—Jorge Luis Borges, Unworthy

(NOT) UNUSUAL

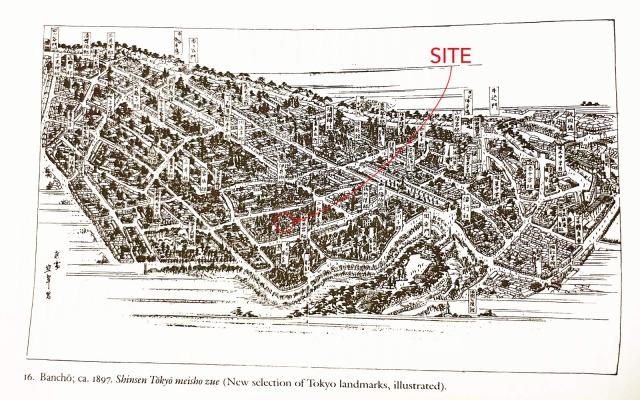

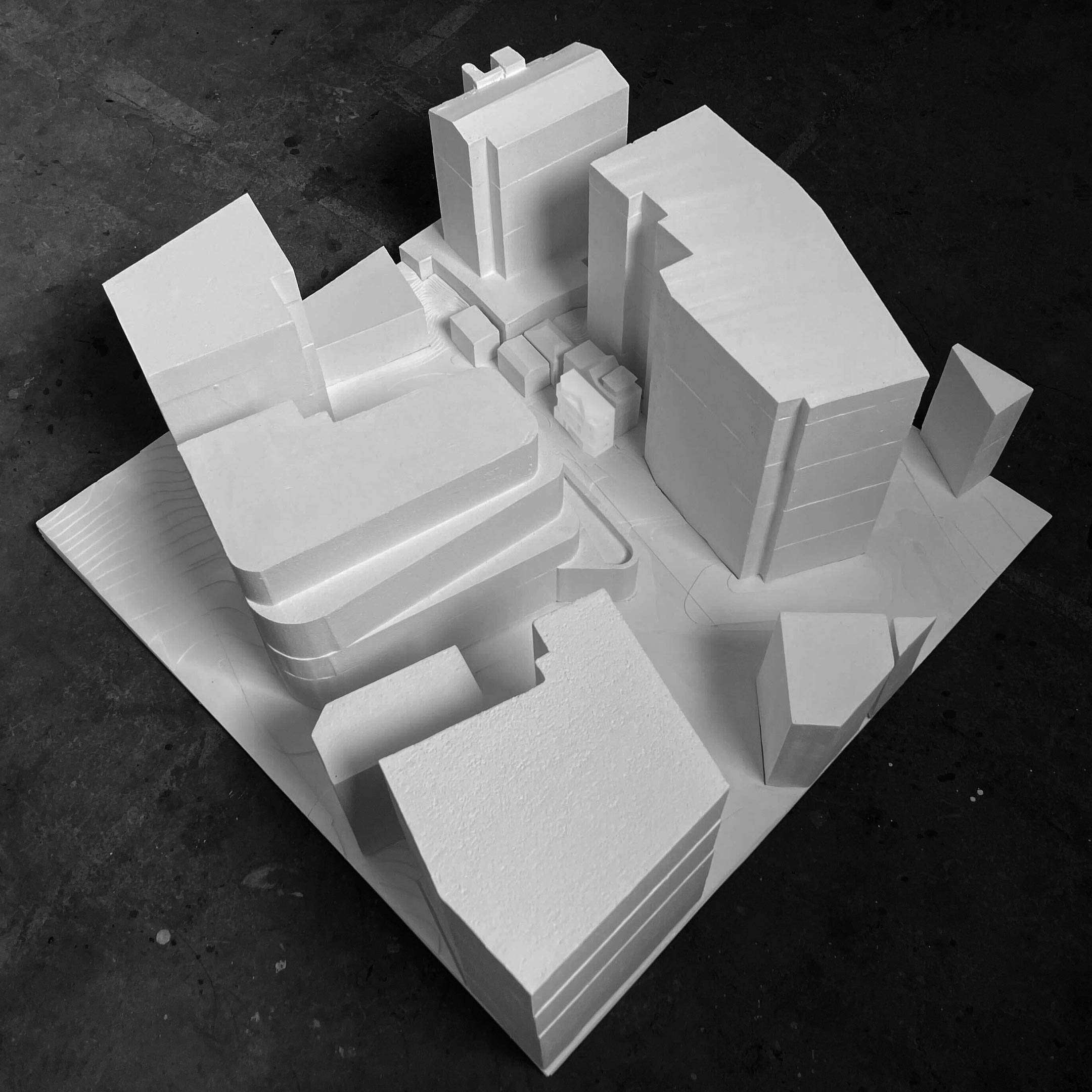

When a Tokyo-based developer of niche-market properties approached FBA with the (not unusual) request to squeeze out the maximum of a site glaringly too small for the overambitious brief for a detached house, we hesitated. Yet what was unusual for such a project was the location: One of five tiny plots to have defied the logic of urban development, the site is a short walk from the British Embassy, which itself sits just across the moat surrounding the Imperial Palace. The fact that there was no reason for this site to exist was enough reason for us to accept.

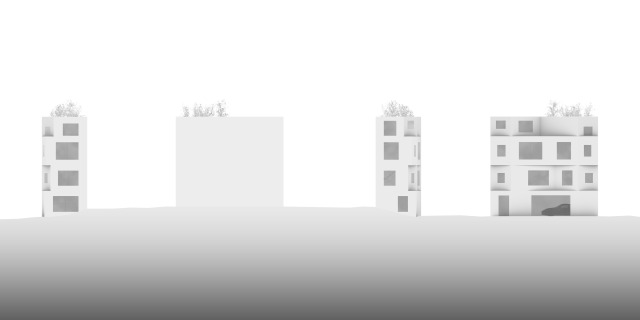

Part of the original Edo’s core, the Banchō has always had a flair of residential generosity to it — unlike the small scale found in the increasingly subdivided and occupied land further and further away from the castle — and in essence still exists everywhere in present-day Tokyo. Here, on the contrary, smallness is a strange anomaly. Not only from the urbanist’s perspective, a little detached house seems ridiculous.

DOWN. THE MOAT OF EDO CASTLE

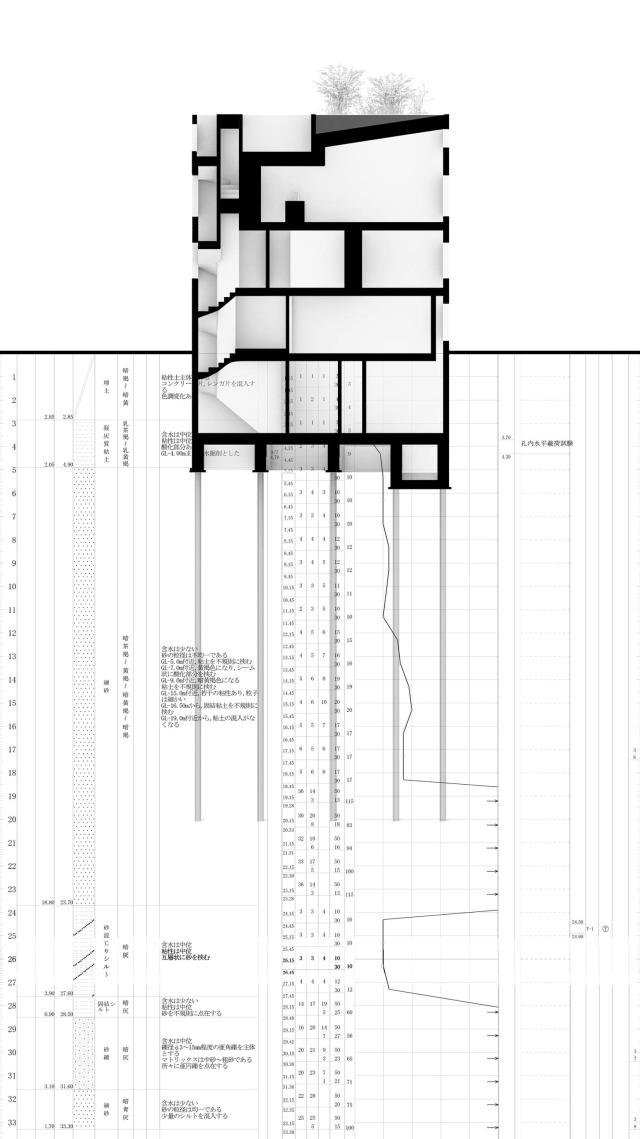

The soil test reveals the site’s history: The land we are standing on is the earth disposed of here during the excavation of the moat around Edo castle. Even for a small three- to four-storey building, piles will need to go 20 metres down. The silver lining: An underground storey (which constitutes the main way to maximise the small site’s allowable floor area) does not trigger additional disadvantages, i.e. piling that could otherwise have been avoided.

We propose an —in this historical context— ironic gesture: the soil of the castle’s moat will be dug up again to make room for the family’s spa.

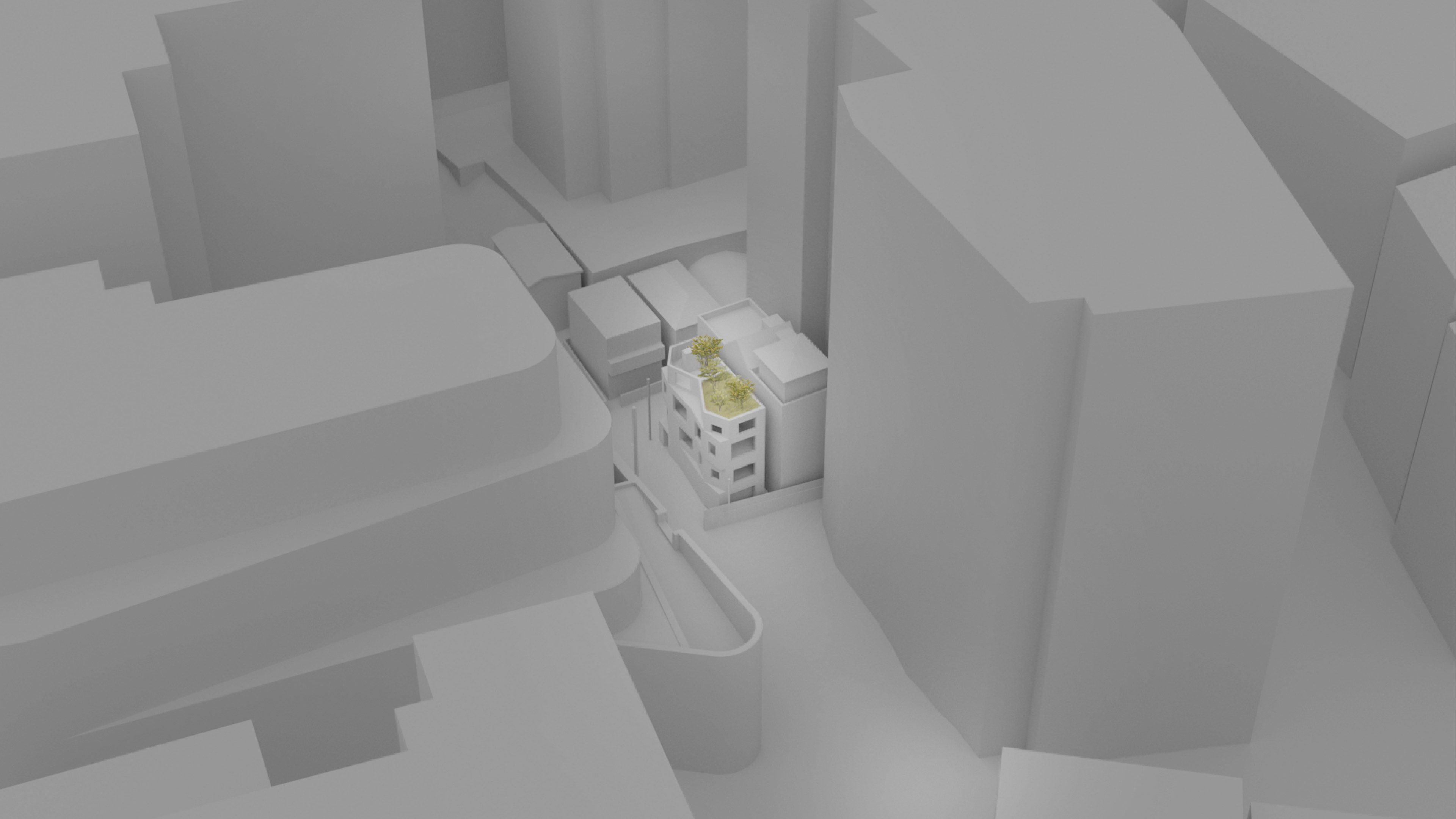

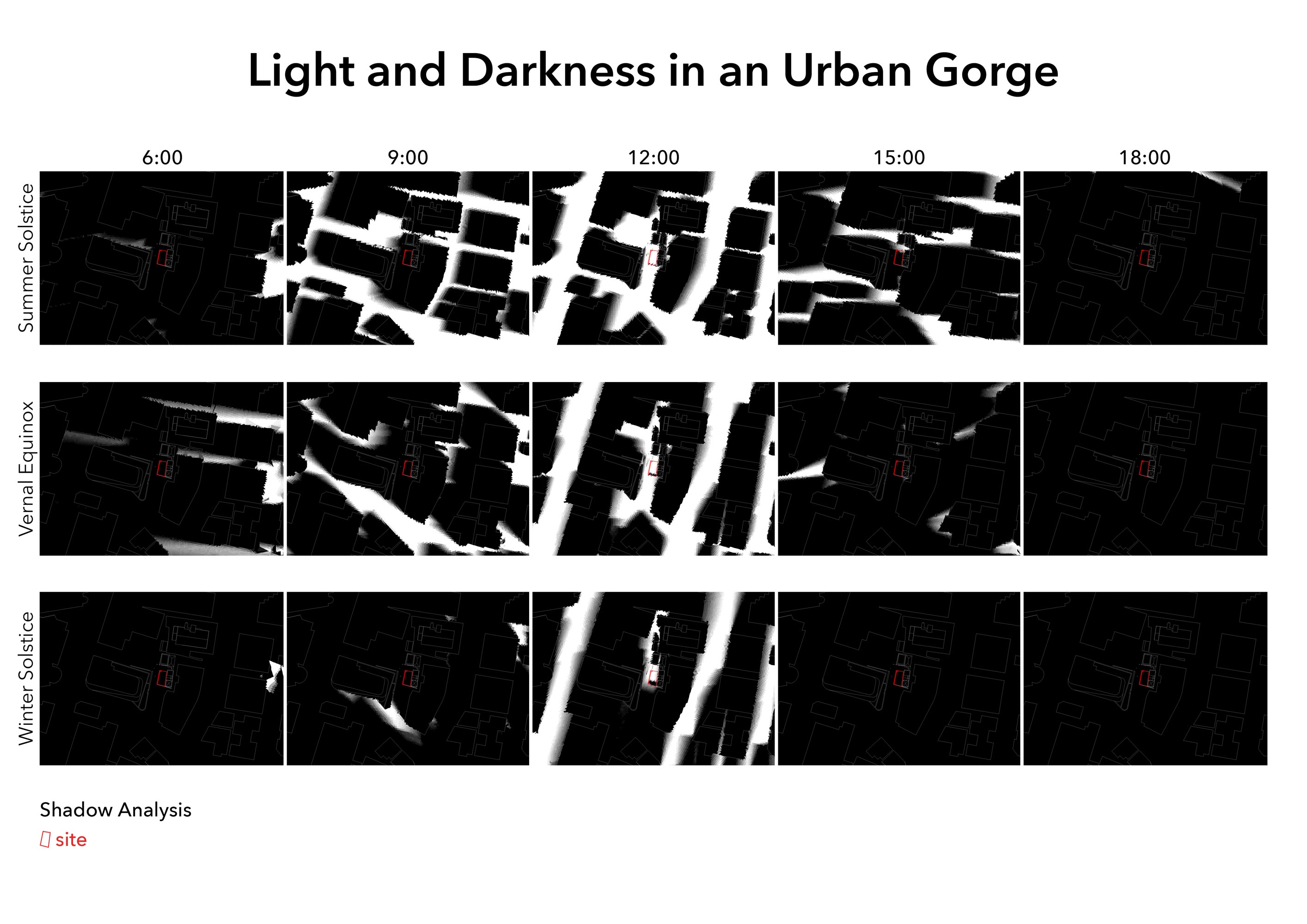

UP. SKY FACTOR

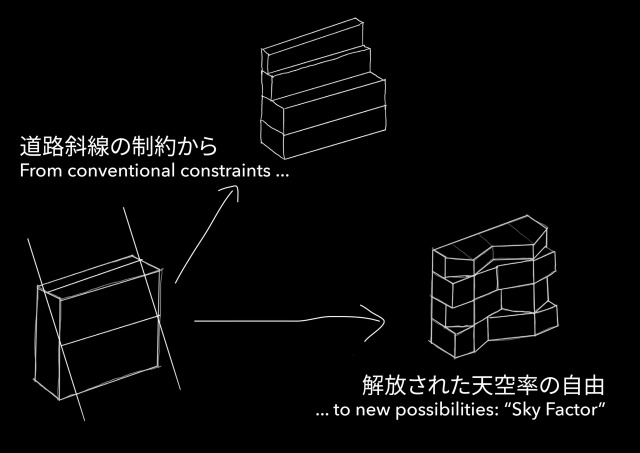

Especially in the context of a small site surrounded by large and close neighbours, to stand any chance of catching light and views means going up. Whereas the neighbouring large buildings —which reflect the location’s historical pedigree— would suggest we could go up, zoning laws make a substantial height unattainable on this small site fronting a narrow (only 4-metre-wide) street.

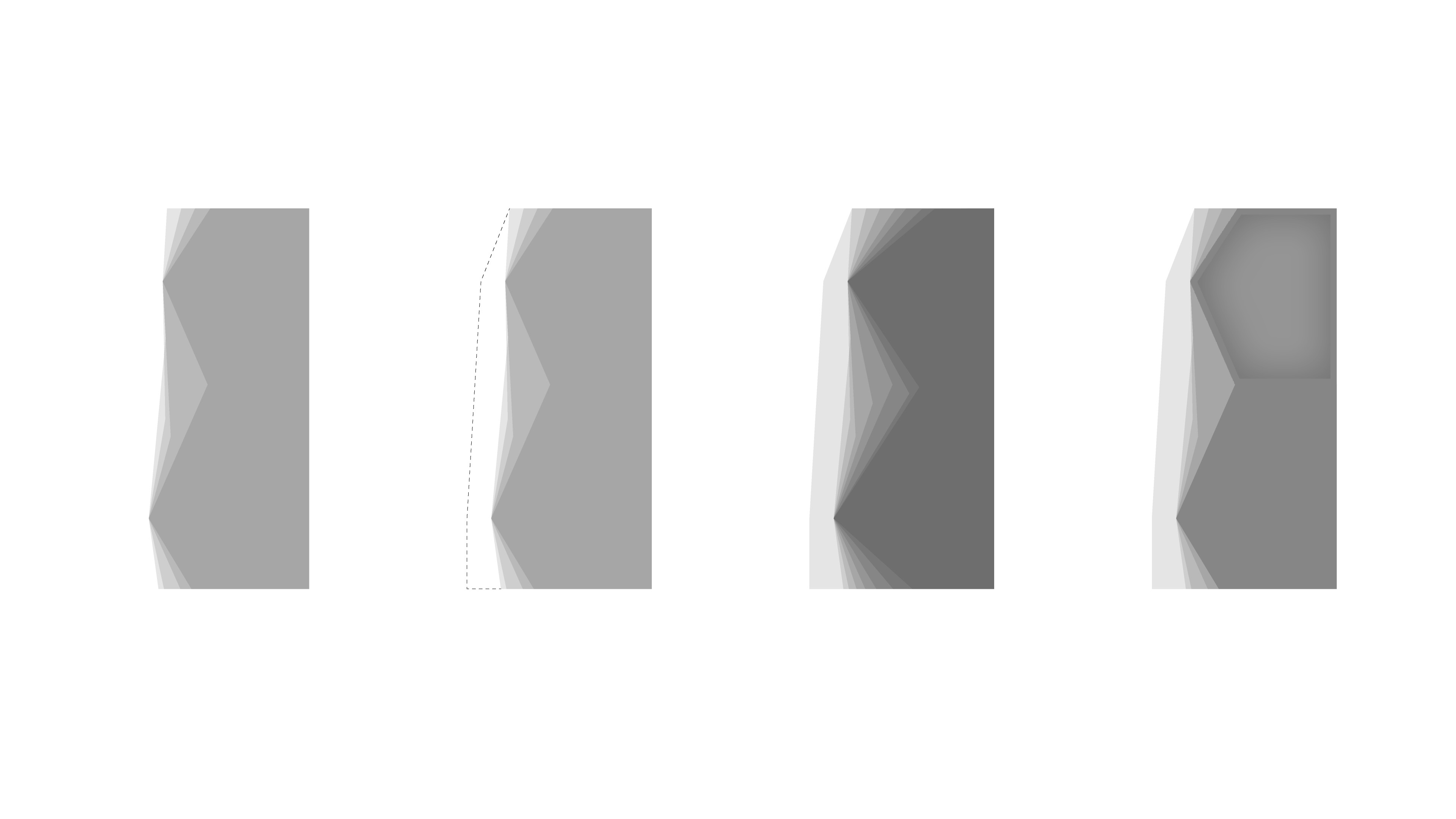

In 2003, in order to counter the inefficient and often expensive-to-construct geometries of slanted lines, an addition to the Japanese building law equipped architects with a new tool: named “sky factor” (天空率), it allows parts of the building to protrude beyond the virtual “street and shadow” lines as long as the total amount of “sky” visible from the street is at least as much.

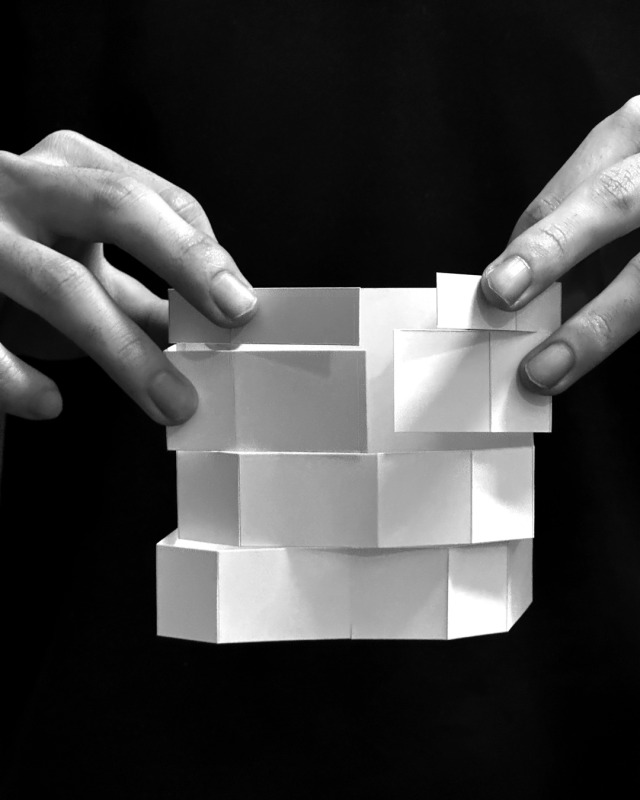

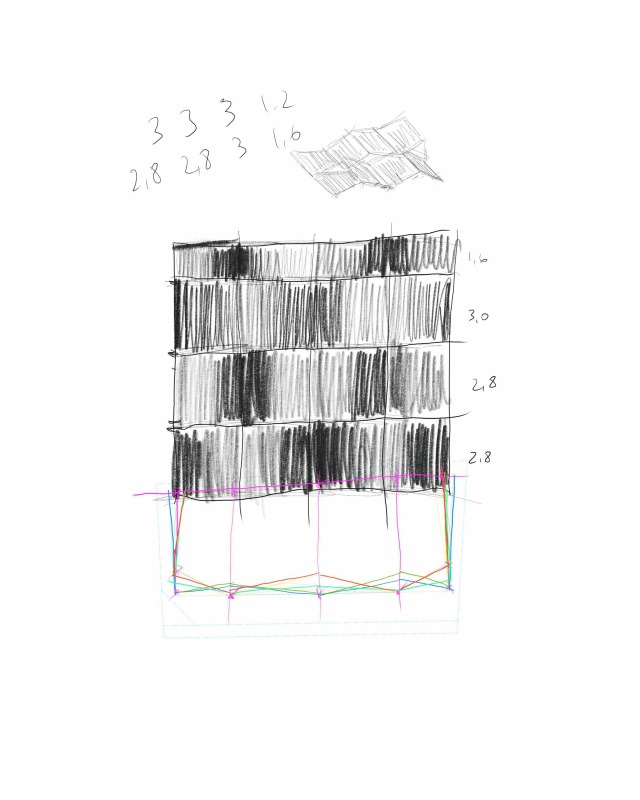

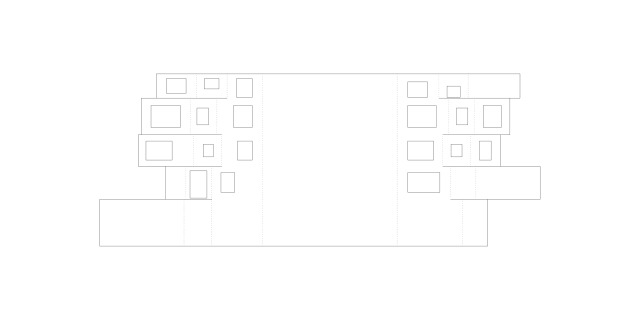

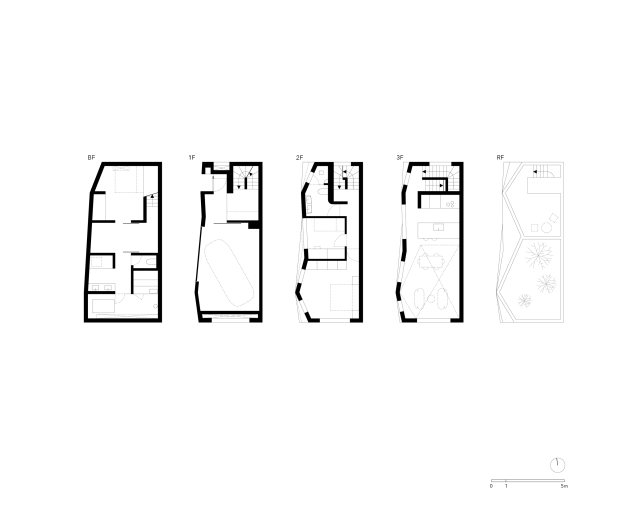

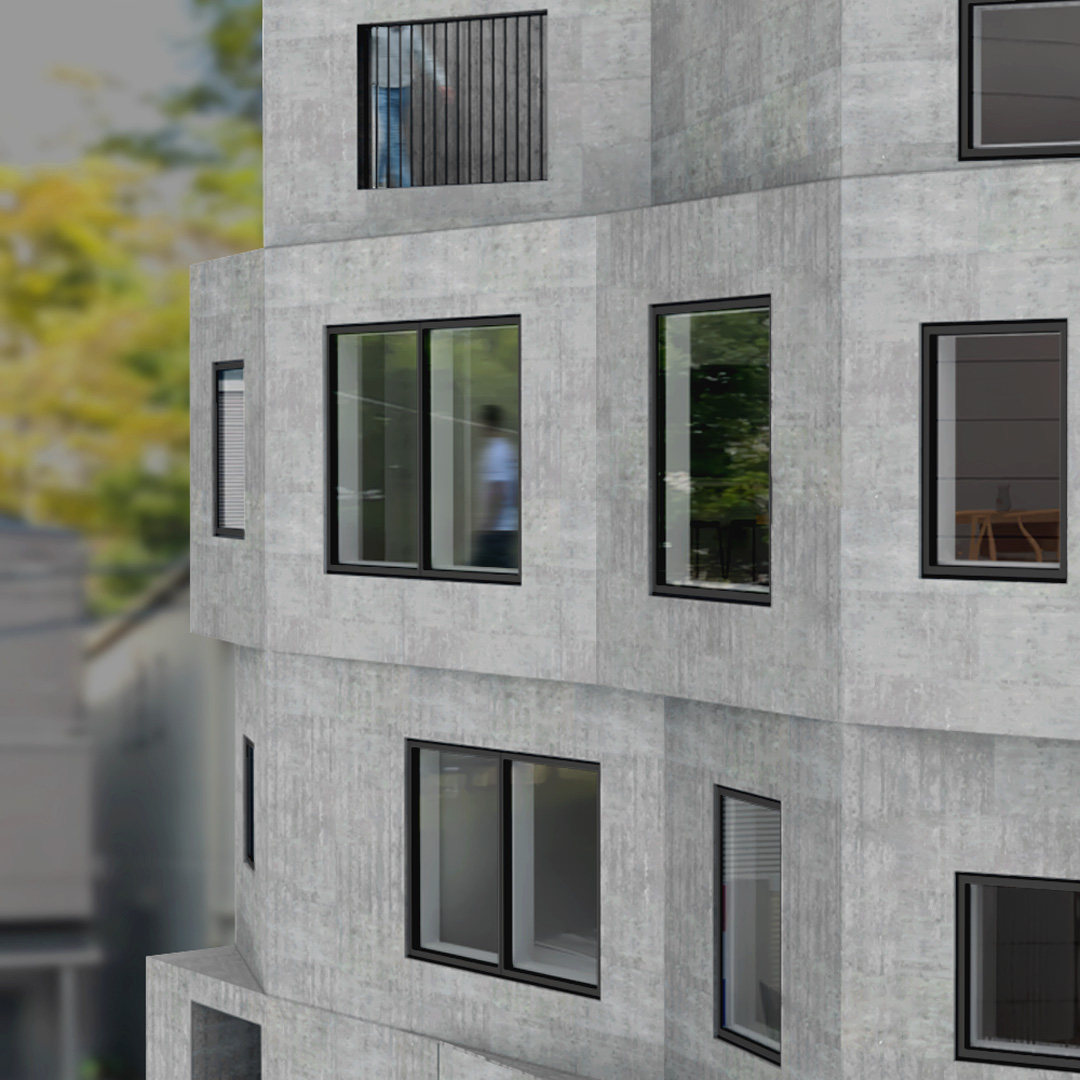

Where conventional regulations would result in smaller floor plans the higher we go up, the Sky Factor gives more freedom to explore larger volumes on the upper levels. As the site has a clear back (the eastern edge) and the remaining 270º panorama of possible views to explore —but none of them a clear winner over others— we devised a strategy to let the north, west, and south elevations find different view angles. Each floor, including the roof terrace, is like a band folded along vertical notches: edges which are allowed to recede or protrude independently in order to reach the optimum solution(s) within the constraints of the “sky factor”.

SNAPSHOT

Developing our own sky-factor-seeking algorithm “Tenkumushi” (天くうムシ) and plugging it into an evolutionary optimisation led to a myriad of unexpected volumetric possibilities.

The eventual outcome is a snapshot of a series of studies sharing the same goals and constraints: maximise the floor area on the upper level; capture views in the site’s limited directions; optimise organisation and distribution of program; minimise structural effort.

In a flexible feedback cycle, where even small changes in the lower levels can yield significant gains for the upper, we were able to explore solutions for a more evenly distributed floor area replacing the ubiquitous small upper floors of the average single-family house in Tokyo. The result is more space in the areas where daily life should happen: at the top, where light and views are best.

In total there are four levels and a roof garden: Entrance and garage at ground level, spa and guest room below (basement), bedrooms above (2F), and at the top level living and dining (3F) with direct access to the garden on the roof.

ABRUPT ENDING

The project was stopped. Despite (or because?) we had maximised what was possible on this restricted site, the developer concluded that the building would not be lucrative enough.

What remains is the story of an anomaly in a backstreet of one of Tokyo’s most prestigious residential areas. And the question whether this site will be occupied with a small building or stay vacant until the small plots are consolidated into a larger block.

Sanbancho, Chiyoda, Tokyo, Japan, 2023—2024

Type

Status

Team

Florian Busch, Sachiko Miyazaki, Reo Shima, Dyro Yamashita, Maki Kishii, Chisei Ye, Felix Spiegl (Intern), Andreas Khamatov (Intern), Sakura Kimura

Structural Engineering: Kawata Tomonori Structural Engineers (Tomonori Kawata)

Size

GFA: 179 m² (+ 33 m² roof garden)

Structure

Related Projects:

- House W in Nakafurano, 2022—2024

- House of Voids, 2022—2024

- House in Sanbancho, 2023—2024

- Nobori Building, 2021—2023

- House I in Arishima, 2020—2023

- House in Nagatadai, 2021—2023

- Villa T, 2021

- I House in Izu-Kogen, 2019—2021

- Hirafu Creekside, 2021

- House in the Forest, 2017—2020

- Y Project in Kagurazaka, 2017—2018

- K House in Niseko, 2015—2017

- S House in Chiba, 2011—2015

- Our Private Sky, 2013

- L House in Hirafu, 2010—2013

- BL Project, 2012

- ‘A’ House in Kisami, 2009—2012

- House that opens up to its inside, 2011—2012

- House in Takadanobaba, 2010—2011

- F&F Project, 2011

- House on the Slopes, 2011

- Toké 7, 2010

- Two Roofs in the Snow, 2009—2010

- House in Karuizawa, 2009

- RG Project, 2009