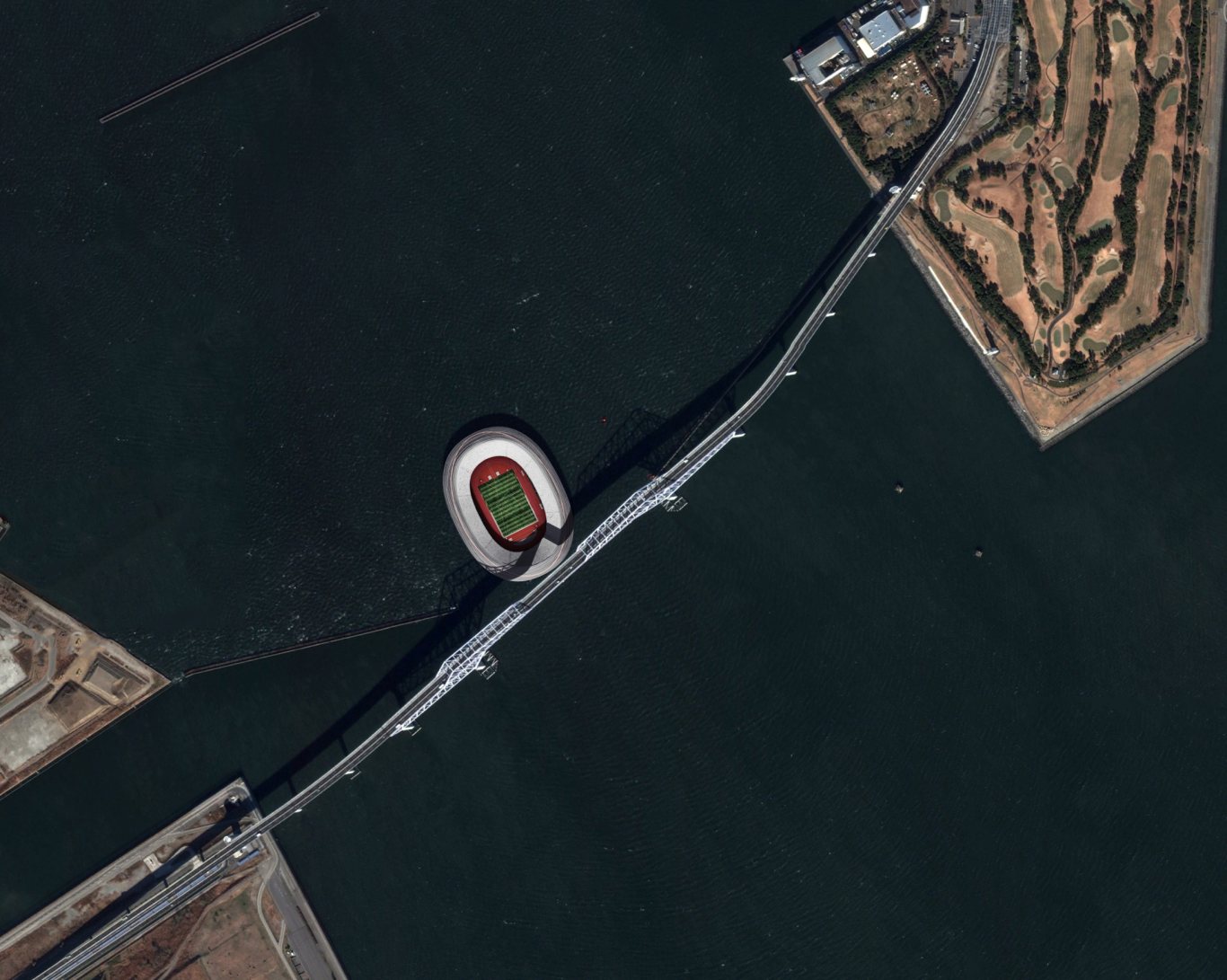

The Floating Stadium

Tokyo & many cities around the globe, 2016—2017

The project behind Tokyo Olympic Odyssey

It is quite sobering to witness that —half a century after some of the best architectural projects of the 20th century kicked off a glorious period of genuinely public projects, many of them embracing the emerging understanding of the fallacy of closed systems— more and more of today’s “grands projets” are mere representations of self-centred myopia.

When in the late 50s —just a little over a decade after the world had almost collapsed under the worst of what nationalism can lead to— Tokyo was selected to host the 1964 Olympic Games, Japan rose to the occasion and showed, on the international stage of the Olympics, the positive powers of a collective spirit.

“Although they were very different characters, the architects worked closely together to realize their dreams, staunchly supported by a super creative bureaucracy and an activist state”.

—Rem Koolhaas and Hans Ulrich Obrist in Project Japan

Anachronism

The years leading up to 2013, when Tokyo was chosen to host the 2020 Olympics, were a different time. Where the reset of the post-war era had brought the necessity of rethinking society as an interdependent organism, self-interest and complacency were now in the driving seat.

A proud committee, recruited from the ages of symbolic bravado, pondered the Olympic stadium and walked —heads high up, eyes sternly focussed on revenue— into the trap of a helplessly overblown brief for the (in their minds indisputably) new stadium. Rather than seizing this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to again usher in a new era, this time around taking up the challenge of the 21st century, any vision was quelled a priori by the decision to bluntly replace the existing with a solution incapable of going beyond convention.

An international competition was held and some of the best of what the architectural world had to offer sent their docile submissions instead of challenging a competition destined to not produce greatness.

Opportunism

When the arguably most emphatically gesturing project was declared the winner, many of those who had up until then been complicit part of the entire undertaking, perhaps surprised by the extravaganza they had unwittingly been involved in, raised a hue and cry.

With success: Two years later, after verifying behind closed doors that a different, new proposal would still make it in time for the Olympics, the winning project was scrapped and replaced with a pro forma competition to find such a ‘new proposal’: less expensive and more in line with preconception. Interestingly, the conditions were now reshuffled, making a temporary add-on to the original stadium a real possibility. Except that the demolition of the original stadium had steamed ahead for months and was about to be completed.

Heterotopia

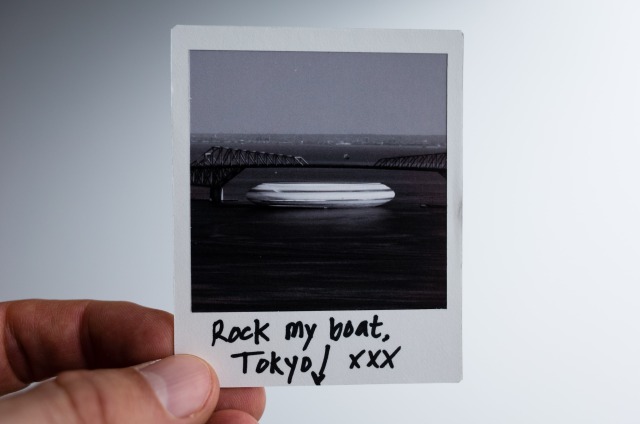

“The ship is the heterotopia par excellence. In civilizations without boats, dreams dry up”.

—Michel Foucault

As it became painfully clear that mediocrity was the last actor standing in this tragicomedy, our thoughts began to drift away towards a future much brighter than what was gradually becoming reality. We allowed ourselves to imagine, as one of many possible saner alternatives, a stadium freed from the baggage of an unnecessarily overwhelming permanence. A site without place, an Olympic stadium made by and for Tokyo, and many of the hosts to follow…

Tokyo & many cities around the globe, 2016—2017

Type

Status

Team

Florian Busch, Tomotaka Yamano, Max Duval, Jamie Eden

Structural Engineering: ARUP

Size

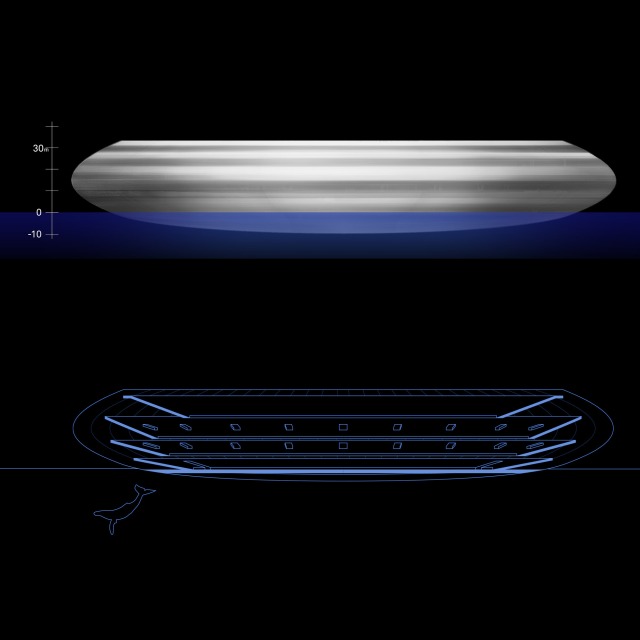

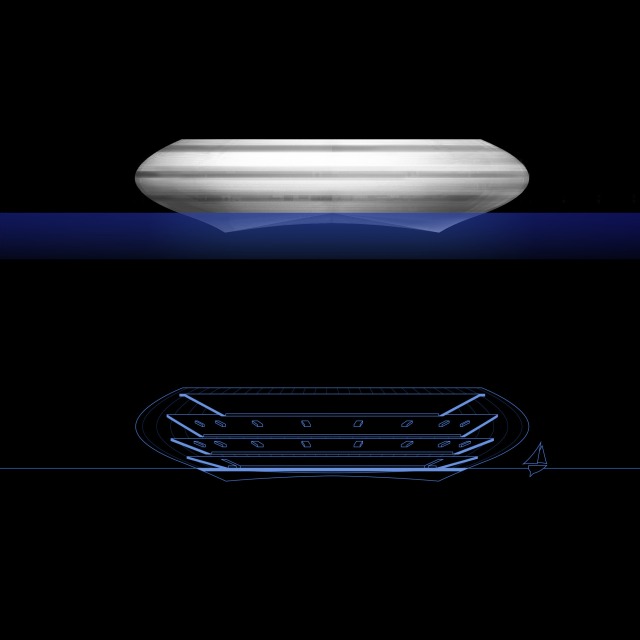

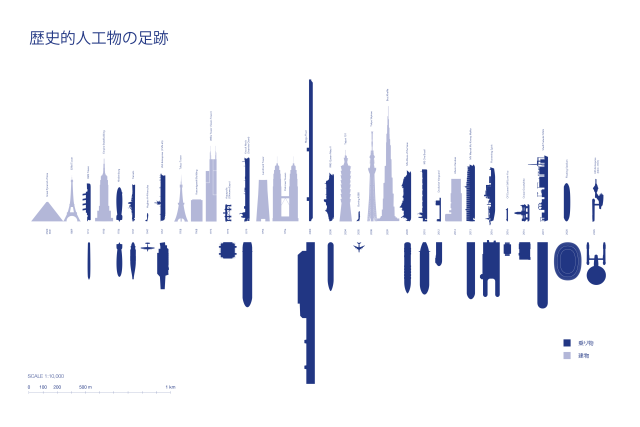

Max. length: 269.72 m

Min. length: 194.96 m

Waterline length: 226.34 m

Height above waterline: 36.44 m

Max. draught: 9.66 m

Total height: 46.10 m

Capacity: 60,000 seats + 20,000 standing (roof) (+ whatever context the floating stadium "docks onto")

Structure

Award

publications

Related Projects:

- Konzerthaus Nürnberg, 2017

- Kiso Town Hall, 2017

- The Floating Stadium, 2016—2017

- Science Island Kaunas, 2016

- Museo de Arte de Lima, 2016

- Itsukushima Miyajimaguchi Terminal, 2016

- Tagacho Community Centre, 2015

- Viaduct Gallery, 2014

- Ota Culture Centre, 2014

- Y Project in Kagurazaka, 2017—2018

- The Floating Stadium, 2016—2017

- BL Project, 2012

- Konzerthaus Nürnberg, 2017

- The Floating Stadium, 2016—2017

- Science Island Kaunas, 2016

- Museo de Arte de Lima, 2016

- Tagacho Community Centre, 2015

- Guggenheim Helsinki, 2014

- Ota Culture Centre, 2014

- Izu Centre for the Traditional Performing Arts, 2013

- Doshisha University Chapel, 2012

- Haus der Zukunft Berlin, 2012

- The Rings of Dubai, 2009